History

Prehistoric Beginnings

Following the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,500 years ago, the shores of the Firth of Forth witnessed the arrival of their first human inhabitants. These were small communities of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, living by fishing, hunting, and gathering shellfish and nuts. Archaeological evidence from across Fife — including the great shell midden at Morton, near Fife Ness, and flint scatters along the Eden Estuary and Tentsmuir sands — shows that these early people established seasonal camps along the coast.

From about 4000 BC, the Neolithic period brought farming: communities built stone tombs, cleared woodland for crops, and raised livestock. Later, in the Bronze Age (c. 2500–800 BC) and Iron Age (c. 800 BC–AD 400), Fife’s landscape filled with burial cairns, standing stones, and fortified hilltops. Among the most important was East Lomond Hillfort, just 15 miles north of Kinghorn, which became a major regional stronghold.

The Pictish Kingdom of Fife

By the first centuries AD, Fife formed part of the Pictish world. The Picts were not newcomers, but the descendants of earlier Iron Age peoples, organised into a network of tribal provinces. Fife itself was known as the Kingdom of Fib (or Fibh), one of the seven traditional provinces of Pictland.

The East Lomond Hillfort appears to have been a key centre of power, guarding the routes between the Tay, the Forth, and the fertile coastlines. Kinghorn, with its farmland, fresh water, and access to the Forth, may have served as a local settlement during this time, though direct archaeological evidence remains limited.

The Emergence of Alba (9th–11th Centuries)

In the 9th century, the Picts and the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata were united under Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpín). Tradition regards him as the first King of Scotland, although modern historians suggest this was more a gradual political and cultural fusion than a single act of conquest. This new kingdom of Alba marked the end of the Picts as a distinct people, though their legacy lived on in place names, stone monuments, and regional identities.

After the union, Fife retained its importance as one of the heartlands of Alba. The old Pictish province of Fib evolved into the Mormaerdom of Fife — an early medieval earldom ruled by powerful local nobles. The Mormaers of Fife were among the most influential figures in the kingdom, traditionally holding the right to inaugurate Scotland’s kings.

The 9th–11th centuries also saw the threat of Viking raids along Scotland’s east coast. While no direct records survive of attacks on Kinghorn, coastal settlements in Fife would have been vulnerable. Defensible sites — perhaps the origins of later fortifications at Kinghorn — may have developed in response to this insecurity.

By the 11th century, Kinghorn lay firmly within the realm of Alba. Its fertile lands and strategic location on the Forth made it a natural candidate for later royal attention, setting the stage for its medieval prominence.

Kinghorn in the High Middle Ages (12th–13th Centuries)

Kinghorn’s rise to prominence began in the 12th century, when the kings of Scotland increasingly looked to Fife as a royal heartland. The area around Kinghorn became a favoured royal hunting ground, valued for its fertile lands and proximity to the Forth, which offered swift access to Edinburgh and Stirling.

This royal patronage led to the construction of a castle at Kinghorn. The precise location remains debated, but evidence suggests it stood near the Loch Burn — the area now occupied by Burt Avenue. By the mid-13th century, Kinghorn had grown into a settlement of real importance.

In 1285, King Alexander III granted a confirmatory charter, elevating Kinghorn to the status of a Royal Burgh — among the earliest in Scotland.

Tragedy struck in 1286, when Alexander III died after falling from his horse while travelling from Edinburgh to Kinghorn Castle. His sudden death, close to the town, left Scotland without a clear heir and plunged the kingdom into a succession crisis that ultimately led to the Wars of Independence.

The Schank Tradition

Local tradition holds that Murdoch Schank, a member of the ancient Schank family of Midlothian, discovered and cared for Alexander’s body after his fatal fall. In recognition of this service, Robert the Bruce is said to have rewarded Murdoch with lands at Castlerigg in Kinghorn in 1319. The genealogy of the Schank family can be traced from this period through to the 19th century (see historical references below).

Kinghorn Castle and the Lyon Family

In the later medieval period, Kinghorn Castle passed into the hands of the Lyon family, hereditary lords of Glamis Castle in Angus. It is likely that this connection led to the Kinghorn stronghold being referred to locally as “Glamis Tower” or “Glamis Castle”.

The castle changed hands several times during the later Middle Ages. At one stage it was reportedly garrisoned by French troops, who used it as a defensive position during conflicts with Reformation forces.

By 1606, the Lyon family’s position was further elevated when Patrick Lyon was created Earl of Kinghorne by King James VI. Contemporary records note that the castle was by then in ruinous condition, with only its walls remaining.

Summary

From the first hunter-gatherers who camped along the coast 10,500 years ago, through the Pictish province of Fib, the union of the Scots and Picts, and the rise of Alba, Kinghorn’s landscape has been tied to the wider story of Scotland. By the 12th century, it had become a favoured royal retreat, a fortified settlement, and later a Royal Burgh. Its castle, long associated with the Lyon family of Glamis, stood as both a symbol of royal authority and a witness to the town’s central role in Scotland’s medieval history.

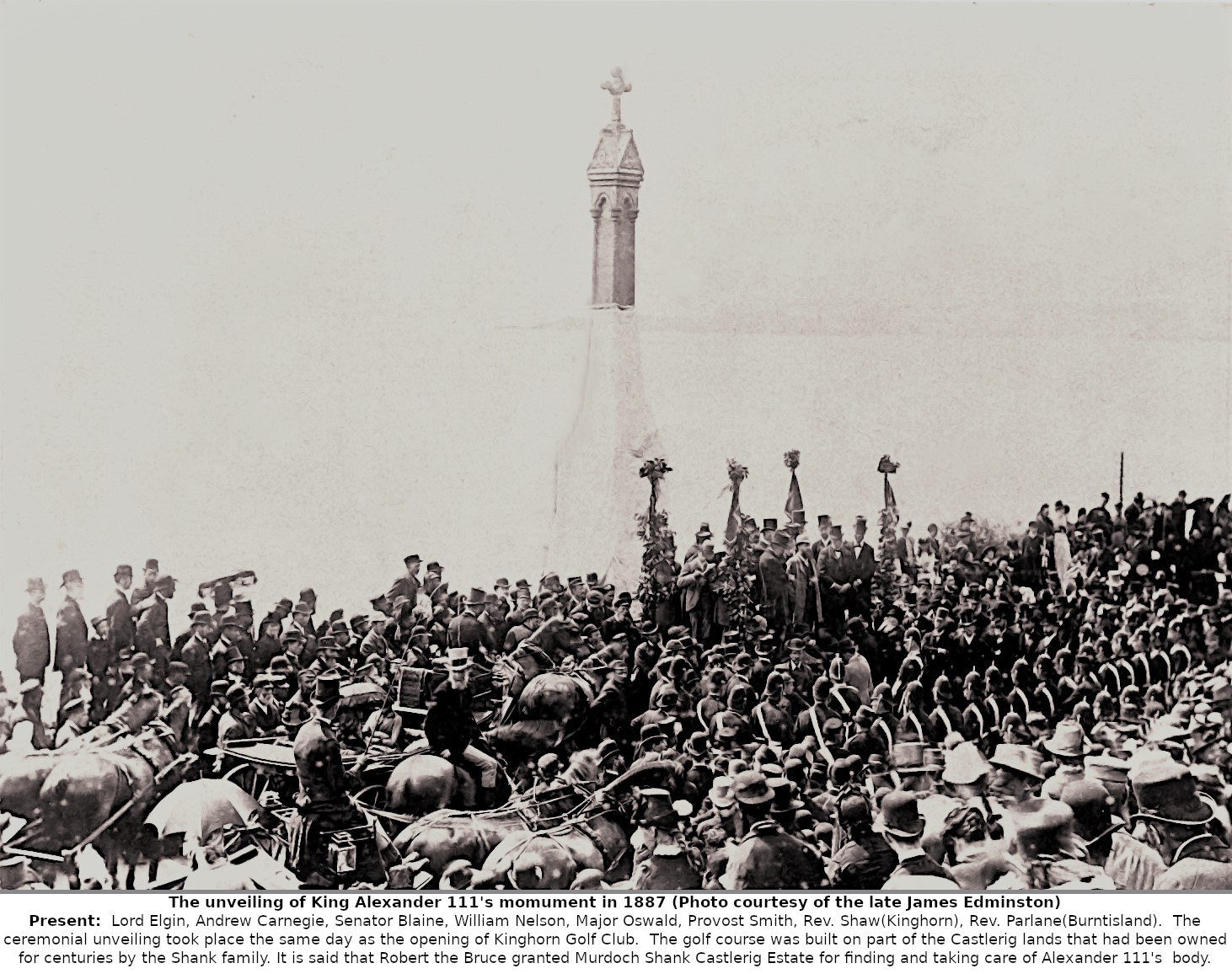

Unveiling ceremony King Alexander III Monument

Prominent figures present at the unveiling ceremony included Senator James G. Blaine, a distinguished Republican who served as the United States Secretary of State in two separate terms, first from 1881 and then from 1889 to 1892. In June 1887, Senator Blaine, accompanied by his wife and daughters, embarked on a noteworthy European journey, exploring various countries. Their final destination was Scotland, where they were hosted at the summer residence of none other than Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie, a Scottish-American industrialist, business magnate, and philanthropist born in Dunfermline, played a pivotal role in the late 19th-century expansion of the American steel industry. His remarkable success led him to become one of the wealthiest Americans in history.

Also in attendance was Lord Elgin, who received the esteemed Freedom of the Burgh of Kinghorn. Subsequently, he assumed the role of Viceroy of India from 1894 to 1899, adding another significant chapter to his distinguished career.

Hover or click to see the

Unveiling Photo

The links below provide access to a wider body of source material. Although presented simply, together they form a small reference library supporting and extending the information on this page.

Kinghorn Historical Society – The local historians have collected a wealth of information and produced the excellent Kinghorn Heritage Trail app, available for mobile and tablet via the links on the Software page.

Fife County Council Archive – Holds extensive Kinghorn Burgh records (1632–1959), including Item No. B/KH: two deed chests of miscellaneous papers and documents. These include a printed translation of the charter granted to Burntisland by Charles I in 1632, voter lists for Kinghorn Burgh (1832–1874), title deeds (1659–1826), and papers relating to Kinghorn School and Philp’s Charity (1823–1846).

The Schank Descendants – The family tree of the ancient Schank family, contributed by Bill Forrest.

Blaeu’s Description of Fife (1654) – Starts halfway down the page. For Blaeu’s engraved 1654 map of Fife, see Old Maps.

Old Statistical Accounts (1794) – The Church’s view of Kinghorn’s social and economic condition.

Sibbald’s History of Fife (1803) – First published in 1710. A substantial reference work (478 pages), opening on the contents page.

A Journey from Edinburgh (1811) – Alexander Campbell – Opens on the Kinghorn page.

Webster’s Topographical Dictionary (1819) – A report on Kinghorn’s social and economic condition.

The Great Reform Act Report (1832) – A short and unflattering document defining the burgh’s boundaries.

History of the County of Fife – John M. Leighton (1840) – Kinghorn coverage begins on page 206.

Old Statistical Accounts (1843) – A further Church review of Kinghorn’s social and economic condition, nearly 50 years on.

Topographical Dictionary of Scotland (1846) – A concise snapshot of Kinghorn.

Barbieri’s Historical Gazetteer (1857) – A particularly informative account of Kinghorn’s place in Scottish history.

Kinghorn Past & Present – A Facebook group for discussion, research questions, and photographs old and new. Easy to join and searchable.

Scotland’s People – The official government source for Scottish genealogical records. See also GENUKI for Kinghorn parish records.

The History of Craigencalt at Kinghorn Loch - by Marilyn Edwards, Well researched and an interesting read.

National Records of Scotland - Their purpose is to collect, preserve and produce information about Scotland's people and history and make it available to inform current and future generations.

Listed Buildings in Kinghorn – There are quite a few.

Kinghorn’s Churches – A short history.

Scotland’s First World War Built Heritage – Contains extensive information on Kinghorn and Pettycur’s built defences.

7th Battalion Black Watch (Territorial Army, WWI) – Early days in Kinghorn (Volume 2: Page:306) You currently may require a VPN to access this USA site